Engaging communities and preventing conflict in Northern Kenya

- Client: Tullow Oil

- Location: Turkana County, Kenya

The challenge : Competition and violence over the spoils of newly discovered oil

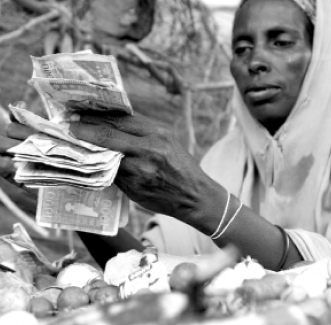

In March 2012, vast reserves of oil were found in Kenya’s Turkana county. The discovery offered newfound wealth for one of Kenya’s poorest and most remote regions, yet its promise also brought a multitude of disruptions and threats; to a sensitive environment, to centuries-old ways of life and the delicate balance of powers between leaders and their constituents.

Oil extraction is controversial. For some the social and environmental impacts make it untenable whilst for others the economic opportunities offered can transform the lives of whole communities. By 2013, the Kenyan Government had awarded the concession to a consortium led by Tullow Oil. By the end of the year, tensions had spilled over into violent conflict over jobs, land and contracts. Tullow realised that their social license to operate was under threat, and that new approaches were required to negotiate fairer distribution of the future benefits of oil.

Oil extraction is controversial. For some the social and environmental impacts make it untenable whilst for others the economic opportunities offered can transform the lives of whole communities.

Our work : Embedded participatory analysis, engagement and action

Following a succession of violent incidents, Tullow requested support from Wasafiri to better understand the drivers and causes, and to identify potential courses of action. Our analysis led to a request to work specifically with local mobile pastoralist communities, subsequently evolving into a four-year participatory process to help pastoralist leaders develop mechanisms to engage more effectively with Tullow and others.

The outcome : Community-owned mechanisms for engagement over key issues such as pasture and land

The discovery of oil triggered a clash of civilisations; Tullow is a publicly-owned commercial exploration and extraction company. They are built around engineering and risk management processes, and work to a Board-driven agenda and the pace of financial years.

By contrast, pastoralist populations operate in loose family groups, without formal shared representation, relying instead on generations-old traditional practices to right wrongs, reach settlement and apportion power. They work to the rhythm of the sessions, the timing of the rains and the pace of generations.

Working with ‘tribes’ as diverse as these, while helping both navigate the multitude of national, county governments interests was, to say the least, a delicate, painstaking undertaking, requiring an approach able to work within and across the entire ‘system’ of relationships and incentives.

The outcome remains embryonic but significant; locally owned mechanisms for pastoralists and Tullow to work more effectively; in resolving disputes, in negotiating contracts and allocating resources. The foundations have been laid for a more equitable share of the spoils.