Insights from the Philea Forum 2024: Leaning into collaboration and systemic approaches

Latest posts

Share:

At the Philanthropy Europe Association in Ghent we discovered that the philanthropic sector is in a state of self-questioning. The big question: how can they restore trust in the communities they serve? The real challenge lies in turning these reflections into practical actions to unlock the sector’s full potential. Read on to see what else we learned.

We all recognise philanthropy’s role in addressing the world’s most complex problems and so I was excited to be one of the bustling bodies of the Philanthropy Europe Association (Philea) Forum 2024.

The forum, hosted at the historic Viernulvier Art Centre in Ghent, Belgium, brought together over 700 attendees primarily from Europe, with some representation from Africa, Asia, and a few other regions.

Despite the vibrant atmosphere, there was a noticeable lack of diversity amongst the attendees, indicating opportunities for greater inclusivity in the philanthropic sector.

Pressing challenges for philanthropies

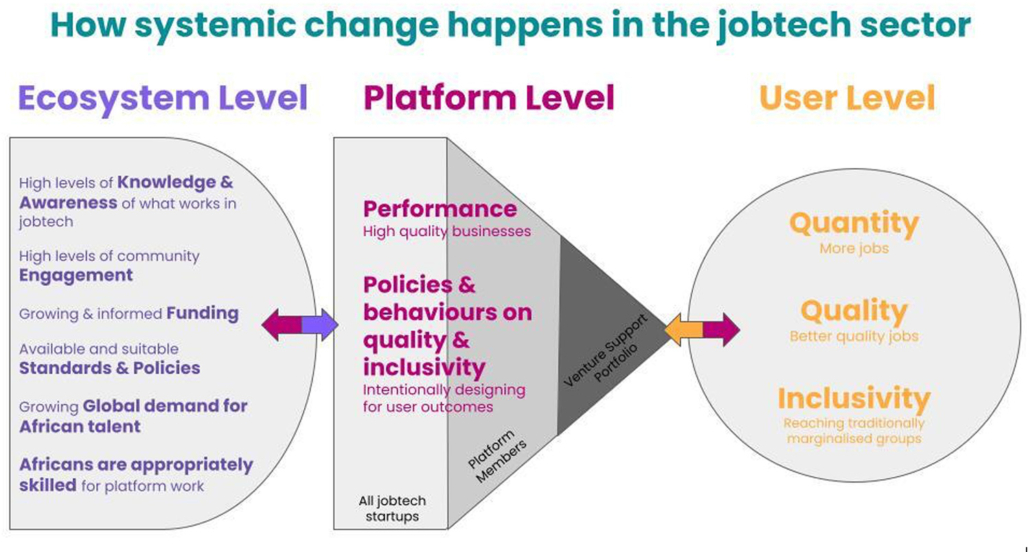

One significant challenge that stood out was the need for philanthropy to adopt a long-term, systemic approach to addressing global issues. Despite frequent discussions about the importance of foresight and systemic thinking, these approaches are not yet widely implemented, hindering effective responses to the ongoing polycrisis.

The sector’s deeply entrenched power dynamics also posed a challenge for foundations and philanthropic organisations when it comes to building and maintaining trust with grantees. There is a pressing need for philanthropy to foster transparent and constructive conversations with grantees.

By truly listening to their lived experiences and understanding their needs and challenges, support can be shaped in a way that empowers grantees to effectively address the issues they are tackling. There is also an opportunity here for the sector to give more recognition to their implementing partners, rather than focusing on self-rewarding.

Additionally, philanthropy’s widespread risk aversion remains a significant hurdle. Despite being in a unique position to be able to take risks, the sector remains overly cautious, limiting its potential impact.

Overcoming board resistance to systemic change, often driven by concerns about risk, power loss, and the measurability of systemic approaches, can facilitate a shift from traditional project funding to more impactful, long-term solutions. This shift can enable those who are closer to the complex challenges to think boldly and experiment with innovative solutions.

What can be done?

The forum showcased several innovative solutions that could, and in some cases already have, begun to address these challenges.

One notable approach is unrestricted funding which offers long-term, flexible support to grantees. This allows the grantees to use funds as needed, allowing them to be agile and adapt to changing circumstances.

This represents an act of trust from funders, acknowledging that grantees are the ones who are best positioned to determine the most effective use of resources.

There was also discussion of the importance of funding long-term initiatives with a holistic approach, providing both financial and non-financial support to frontline organisations. This encourages bold and experiemntal approaches to addressing complex issues.

Moving away from rigid impact measurement and towards learning-focused evaluations was another key strategy discussed.

Establishing learning goals in collaboration with grantees, rather than demanding hard data and KPIs, can lead to deeper insights and more meaningful assessments of impact. This approach encourages a culture of continuous improvement and shared learning between funders and grantees.

Reporting to boards through human-interest storytelling and individual/specific examples of success or lessons learned, rather than relying solely on numerical data, can help shift board perspectives towards a more systemic way of looking at things.

An inspiring keynote

A particularly inspiring moment was the keynote speech by Ethics Researcher Ezekiel Takam at the closing plenary. Takam invoked the philosophy of Ubuntu, advocating for philanthropy to embrace connection, inclusion, and the collective power of all actors working together. This resonated deeply with me reflecting the ethos of Wasafiri’s vision.

The Forum highlighted a growing need for the philanthropic sector to embrace change, collaborate, and adopt innovative strategies to effectively address the complex challenges of our time. Concrete steps need to be taken in this direction.

None of these things will be easy or comfortable. It will challenge the status quo and there will be opposition from those the current model is working for. But by slowly shifting the needle, philanthropy can unlock its full, huge potential and and contribute to lasting change.