Preventing violent extremism in East Africa

How can vulnerable communities across East Africa be supported to respond more effectively to the threat of violent extremism?

Our Experience

Since 2014, Wasafiri has been working with governments and communities across East Africa to better understand the nature of violent extremism and to help catalyse new efforts at designed to tackle the threat. Our work has included;

- Monitoring, analysis and reporting of events, programmes and policies.

- Identifying at-risk groups and networks of positive influence around them.

- Examining under-researched issues, such as the role of women, the private sector, or gangs in extremism.

- Facilitating the design of new initiatives designed to prevent and counter extremism

- Engaging with communities and government representatives to strengthen local capacities, strategies and plans

Our experience has taken us to all corners of East Africa from Somalia to Mozambique. We have learned deeply from those at the heart of the system; from remote communities to national policy-makers, and it continues to galvanise our work to strengthen resilience across the region.

The Challenge

Complex macro and micro factors drive people into violent extremism. Our research across the region has revealed a messy combination of factors which can all converge in unpredictable ways to drive people toward violent extremism (VE). These include structural factors (such as inequality/marginalization, weak governance and security, poor education, unemployment), social factors (such as pressures from peers, family members, social networks) and personal factors (such as family crisis, personal trauma). Ideology can also play a role. We see these factors playing out in highly contextual and localised ways across the region, varying considerably between communities and groups.

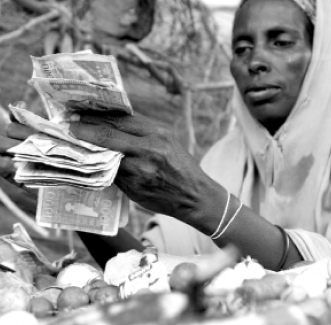

The nature of the threat is constantly evolving. The appeal of VE is a radically dynamic phenomenon, attracting vulnerable people by exploiting personal grievances, adapting to volatile local contexts and offering compelling narratives. We have found that recruitment campaigns, both in-person and online, are strategically patient and highly tailored to socio-economic and educational status, encompassing a broad spectrum from university students, those who have been abused by state security forces, to men and women simply struggling to earn a living.

It is tempting, but dangerous, to lump all extremist organisations together. Identifying their distinguishing features, their approach, ideology, or reach, is both difficult and uncertain. Communities in Kenya for example, are most likely to refer to the Somali group Al Shabaab, while evidence is emerging that ISIS and other groups have increased their reach.

The collective response to VE is itself unpredictable; regional governments and the international community’s appetite to move from lofty rhetoric to meaningful policy and sustained action shifts according to the success of terror groups and the whims of political expedience.

Better coordination and shared learning are required

Initiatives designed to Prevent or Counter Violent Extremism (P/CVE) remain relatively nascent, and their impact is limited, sometimes by design; ad-hoc or one-off interventions which fail to scale, or larger programmes which apply one-size-fits-all approaches. Weak coordination across borders doesn’t help; unlike many other sectors – agriculture, health or education for example – the international agenda on P/CVE is relatively disjointed. UN leadership in the P/CVE space is light, confined to recommendations rather than joint action, with states unwilling to cede power on national security priorities. The absence of any universally agreed definition of VE points to this lack of unity.

The result is a disparate profusion of initiatives led by East African and Western governments across regional and national hotspots, but with varying degrees of coordination and cooperation.

More locally, we have seen the traditional actors, such as the larger and better known national civil society organisations, can struggle to identify, reach and engage with truly at-risk individuals. Further, religious leadership across the region is diffuse and disconnected, with few centralised or representative institutions able to support imams and sheikhs to respond to the threat in a coherent manner.

We’ve been working across East Africa to better understand the nature of violent extremism and to help catalyse new efforts at designed to tackle the threat.

The State of System Change

Violent extremism is an extraordinarily complex phenomenon. Below, we take a systems-based perspective on the quality of collective efforts to respond to the threat across East Africa; and ask “what next?” is required to build on progress.

Building Shared Understanding: Increasing clarity on problems but not solutions. A skewed lens?

Compared with the Middle East, relatively few studies on violent extremism exist in East Africa. Most research is largely based on surveys of community perceptions which tend to focus on problems such as the lack of job opportunities, discrimination of minorities, and failings in governance. These factors affect millions of young East Africans and certainly do feature in reasons for joining VEOs. However, and while progress is being made, much more needs to be done to understand the social and personal factors which trigger a tiny proportion of these young people to act on their frustrations by joining an extremist group.

More importantly, even less is known (or shared) about the kind of interventions most likely to prevent individuals from being recruited. Publicly available literature is all-too rare, often due to the sensitivities of the information they contain, and the restrictions placed on wider distribution by donors, and there are few examples of ‘scalable’ programmes backed up by evidence to prove their preventative effects.

Wasafiri’s research model, honed over thousands of interviews across the region, emphasizes the need to identify at-risk individuals based on their ‘embeddedness’ in existing social networks which have links to VE activity or support. By focusing on the unique experiences of these individuals and the context-specific drivers of VE in their local communities, we’ve found we are better able to understand patterns of recruitment, and opportunities to disrupt them.

Securing Commitment: The challenge of aligning diverse (and often competing) interests

The dizzying array of factors which contribute to recruitment are the domain of many actors. And therein lies a central challenge to effective P/CVE. Aligning the interests of government, business, civil society, the media as well as those of foreign donors is a mighty challenge. Across and within these organisations lie vastly different interests, agendas, constituencies, resources, mandates and so on.

Closer to the issue, international and domestic policies and programmes tend to be subordinate to the counter-terrorism (CT) agenda. CT often prioritises a more hardline, security driven approach that can undermine longer-term, more nuanced P/CVE efforts in communities, and even worse, inflame local grievances against the state. The consequences of such policy gaps and tensions are real; the lack of a clear policy on the treatment of returnee fighters in Kenya, for example, means that those willing to disengage live in fear of being targeted by security forces.

Changing the Dynamics: Diverse and small-scale interventions are showing early signs of promise, but how to scale?

Evidence of what works is scarce, hindering efforts to replicate and scale successful interventions. This is starting to shift, as P/CVE programmes take root and generate tell-tale signs of results, planned or otherwise.

For instance, our embedded research and community outreach efforts are beginning to demonstrate the value of interventions which assist those individuals and groups who engage regularly in person with at-risk youth in their own communities. By gently nourishing these grassroots efforts over time with the right blend of skills, resources, ideas and networks, we have helped shape conditions which have deterred individuals from joining VEOs. This shift away from more conventional interventions that focus on broader and more superficial definitions of who is at-risk toward a greater focus on the individual and their closest social networks has been game changing at a micro-level. But the costs of time, access and resources make it a model hard to scale.

Enabling Coordination: Mechanisms for coordinating action are emerging, but need support to generate momentum.

Kenya’s National CVE Strategy provides a helpful starting point for enabling more coordinated action from across the assembled P/CVE actors. Some counties in Kenya (such as Mombasa and Kwale) have developed county level action plans which show promise for translating national intentions into county actions. Our sense is that the process was particularly useful for reinforcing the role of civil society (which has often had an uneasy relationship with the state), and for creating important platforms for at-risk youth and their families. But the plans have a long way to go yet before they are adequately resourced and implemented.

Uganda appears to be following suit in developing its own National CVE Strategy. (Wasafiri is among other civil society actors who are helping to shape this work). Again, generating shared commitment, supported by strong coordination and sufficient resources remain questions waiting to be answered.

Elsewhere, valuable forums have emerged to support practitioners and researchers exchange insights and advice. Wasafiri has helped convene one such example; the CVE Research Forum, comprising donors, researchers, and practitioners, meeting monthly in Nairobi.

Regionally and beyond however, evidence of momentum is low. The UN is struggling to assert its leadership and there is no universally agreed definition of violent extremism. In 2016 the UN did adopt a plan of action on P/CVE that includes 70 recommendations for states, and UNDP recently published a compilation of research across 6 countries in Africa, which highlighted urgent needs for governance and security sector reform. The African Union’s convening body IGAD established a CVE Centre in Djibouti with donor support in April 2018, which is focused on information sharing and capacity building across the region. These efforts however have some way to go before translating into more coherent action on the ground.

Augmenting Learning: Information flows need to empower those on the front lines.

Despite the gaps, the body of knowledge from which to design and implement more useful interventions is growing. However, our experience suggests that research and learning efforts are often extractive and do not sufficiently serve the teachers, imams, police officers, families and chiefs working on the front-lines. We see the right information, shared in the right ways, as a powerful lever of change.

To help redirect this flow, feedback loops need to be designed into programme design from the outset, ensuring that research and evidence flow outward and downward. Learning processes could be better designed, involving those who stand to benefit most. New approaches to monitoring emergent outcomes should be tested and scaled.

What Next?

More is now known about the factors that lead to violent extremism and how it can be prevented, but more must be done to scale what works. Below, we offer our recommendations on what can be done next;

Efforts must focus on enhancing accountability and respect for human rights among security forces in order to build greater trust with local communities. Conventional ‘training and equipping’ models are not sufficient; sustained community awareness, engagement and dialogue is necessary to strengthen platforms for both police and local communities to come together around issues recruitment and radicalisation. Working more informally through existing community groups, such as sporting teams or parent-teacher associations, could help establish safe spaces for engagement.

In Kenya specifically, reforms must also extend to a clear policy for the reintegration of returnees and a fairer application of the procedures for allowing access to the all-important Identification Cards

County plans are not enough. Considerable effort is required to assist and motivate local administrations to respond more effectively to the threat. The mandate and organisation of local governments to do so varies between countries, but in countries where the mandate is devolved sufficiently to the local level, officials should be supported to integrate P/CVE plans and resources into local development agendas.

The evidence is clear – CVE interventions must be informed directly by those (predominately young people) who are most at-risk of becoming influenced or recruited by extremist groups. Traditional civil society actors and conventional programming approaches all too often do not reach those most at risk. There are good reasons for this – they are usually the hardest to find and engage. But their families, peers and local leaders often can. But the all too frequent failure to take the hard road will continue to lead to shallow, weaker programming.

The expanding ‘youth-bulge’ is galvanising governments and donors alike to invest in youth economic capability and skills. This presents new opportunities for situating P/CVE initiatives targeting young people at risk within these broader programmes. Such an approach would yield multiple benefits; for referring at-risk populations to new empowerment opportunities as well as generating new insights into how to influence the attitudes and behaviours of such groups. A further advantage lies in the potential for reducing stigma and tensions in communities where opportunities for many are scarce. But it won’t be easy; programming in this way will require careful, sensitive work across disciplines. And such an approach does not remove the need for a social networking model to identify and engage with at-risk youth in the first place, but it could prove powerful.

Beyond the conventional approaches to capacity building, we see real potential in supporting and equipping those influencers doing the hardest work of tackling extremism:

- Responsive religious leadership. Donors, practitioners and researchers need to develop more ‘religious literacy’ and understanding of narratives and learnings in Islam, and the other great faiths to approach capacity building from more nuanced and faith-based perspective.

- Family members. Research has shown the impact that mothers can have upon sons in deterring them from the appeal of extremism. We suggest more work should be tailored toward understanding how best to equip mothers, fathers and siblings as positive influencers of at-risk individuals.

- Community influencers. From elders, teachers to business owners, our research has consistently highlighted the need to find new, creative ways to identify and empower key members of the social networks binding vulnerable people to constructive influences.

The work of tackling violent extremism at its roots is painstaking and uncertain. Delicate relationships, foundations of trust, emerging relationships are quickly disrupted by the withdrawal of funding or unforeseen shifts of policy. Donors and partner governments alike must steel themselves to staying the course of through their provision of funds and policy direction.

At this early stage of tackling violent extremism, the need for building out a robust body of evidence cannot be overstated. Coordinated efforts are especially important to protect against duplication in over-researched communities (such Nairobi Eastleigh, Mombasa Likoni) where ‘respondent fatigue’ is undermining support.

VE is a transnational issue. It does not respect national borders or policy frameworks. Much greater effort must be directed toward strengthening networks of practice across the region, facilitating exchanges and information sharing between academics, researchers, practitioners and governments.

Definitions

‘At-risk’: Wasafiri uses the term ‘at risk’ to mean susceptible to, attracted to and/or likely to join a Violent Extremist Organization (VEO).

Youth:’ The term refers to people aged between 18 and 30 years old.

‘Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism) (P/CVE):

These terms are used interchangeably by Wasafiri because existing initiatives we work on are categorised primarily as ‘CVE’ programming by donors, whereas we believe that most of our work is aimed at preventing violent extremism.

‘Violent Extremism’ (VE): material and/or immaterial support for or engagement in violent acts justified by an inflexible and uncompromising ideology. The extent to which individual actors or supporters embrace this ideology may vary.

Tools & Resources

Tools & Resources

Graduation from Poverty in Kenya – Perspectives from Stakeholders

Insights and experiences from stakeholders involved in poverty graduation in Kenya.

Graduation From Poverty National Workshop

Highlights from the national poverty graduation workshop designed to harmonise graduation efforts at scale.

Government and Donor Key Messages

Headlines from Kenya’s Social Protection Secretariat in tackling sustainable economic and social empowerment for the ultra-poor.

Defining and Better Targeting the Ultra-Poor in Kenya

A study produced by Wasafiri designed to strengthen policy making and graduation programming.

Country Scoping West Pokot

A scoping study produced by Wasafiri of socio-economic inclusion efforts for the Working Group on Ultra Poverty in Kenya.

Sustaining Poverty Escapes in Rural Kenya

A report from ODI examining the means for interventions and approaches in Kenya that aim to enable poor households to escape poverty and remain out of it.

SCI Youth migration/ livelihoods study

A review of challenges and opportunities facing youth migrating to urban areas in Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia.