Transforming Youth Employment with Systems Change in Africa

Latest posts

Share:

Originally posted at Jobtech Alliance

The looming jobs crisis for young people in Africa

In the next 10 years, African countries will add more people to the workforce than the rest of the world combined. However, while 10 to 12 million youth will enter the workforce each year, only three million formal sector jobs will be created.

There simply won’t be enough jobs for the people that want them. This shortage of quality jobs, particularly for Africa’s burgeoning youth population, risks creating high levels of unemployment, social and economic disparities, and potential migration pressures.

Jobtech Alliance believes this mismatch between youth skills and market demands would hamper productivity and persistent unemployment would pose risks of social unrest and undermine innovation and development potential.

Without the addition of significantly more quality jobs for young people, Africa will not achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

Transforming youth employment programming through jobtech and systems change

The world of work is undergoing significant changes, prompting development actors to experiment with new approaches in youth employment programming. This shift is driven by the necessity to adapt to evolving economies and a rapidly changing technological landscape, coupled with mounting evidence challenging the effectiveness of traditional labour market interventions.

Two prominent trends have emerged in recent years to address these challenges:

- Applying systems change methodologies to labour markets. ‘Systems change’ is an intentional approach to transform the underlying structures, processes, and relationships within a system to address persistent challenges and achieve positive outcomes. In the context of labour markets and youth employment programming, systems change involves re-evaluating and reshaping the complex web of interconnected elements that influence employment dynamics, such as policies, institutions, education, and economic structures. We see it as a holistic, adaptive, and long-term approach that emphasizes partnering with relevant market actors to change the way the system works for young job seekers (Market Systems Development for Employment).

- The emergence of jobtech which leverages technology to enhance job access, delivery, and productivity. The essence of jobtech are platforms that connect people to work, or which enable them to manage their livelihoods. This includes gig-matching platforms such as ride-hailing, e-commerce, and online job-matching (see Jobtech Alliance’s taxonomy of the jobtech sector in Africa). It is becoming a cross-cutting theme around everything to do with the future of work and how people find work. It is estimated that 30-88 million Africans will earn from jobtech by 2030.

Jobtech Alliance: pioneering systemic solutions for job creation in Africa

Founded in 2021, Jobtech Alliance recognises the potential for ‘jobtech’ to transform the generation of quality, sustainable jobs and do so at a continental scale. The heart of our job-generating ecosystem is jobtech platforms.

We are building an ecosystem around inclusive jobtech to create viable, scalable platforms which provide quality jobs for Africans. We recognise that technology won’t solve youth unemployment on its own, but it plays a crucial role in shaping the skills and opportunities for future generations.

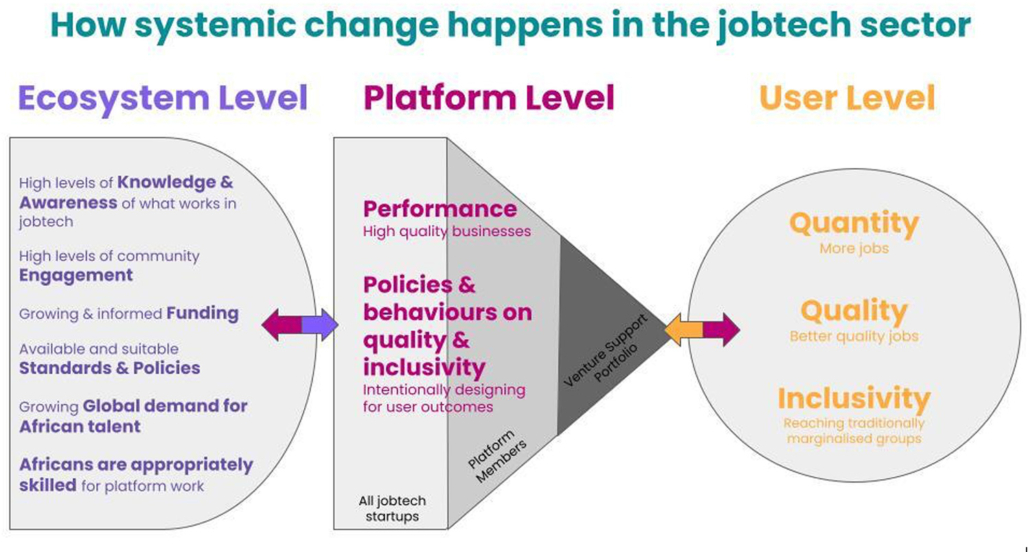

We use a systemic lens to ensure that jobtech interventions go beyond isolated solutions, contributing to shaping the jobtech sector for increased sustainability and inclusivity. Overall, this comprehensive approach acknowledges the changing landscape of youth employment and maximizes the potential impact of jobtech as part of a broader systemic strategy.

Practically, this means we are working across multiple fronts to shift the dynamics of the current jobtech system, including:

- Building awareness and knowledge of jobtech, and what works in jobtech: While ‘Jobtech’ gains recognition, a weak understanding persists. Elevating awareness is vital for unlocking the sector’s full potential. We conduct research and host a blog and newsletter to keep the community informed.

- Nurturing an engaged, informed, and inspired community: Establishing a cohesive community is crucial, and bridging gaps between interconnected stakeholders and fostering collaboration, is essential to share learnings and drive innovation. We host a large community with over 1000 stakeholders including jobtech startup founders, investors, and others to connect and collaborate around our shared vision, with a range of events to connect stakeholders.

- Nurturing appropriate policies, standards and tools: Striving for policies that consider and align with systemic dynamics is imperative for effective jobtech sector development. We’ve worked with the International Labour Organization to develop a standard tool (currently being piloted) to assess quality of work on jobtech platforms from a user perspective.

- Fostering a funding network: The jobtech sector faces funding setbacks, with a notable decline in investment. Addressing this challenge is critical for sustained growth and impact. We’re building a Jobtech Investment Network of venture capital and philanthropic funders to ensure that informed funding reaches the right startups.

- Venture support: Acceleration activities (through advisory and management support as well as capital) for high-potential platforms that can propel the entire sector, fostering successful businesses, generating excitement, and attracting more entrepreneurs and investors. We currently have a portfolio of almost 20 platforms we’re working with.

- Stimulating global demand for African talent: Jobtech’s essence lies in connecting labour demand (and products and services) with supply. In Africa, addressing the employment shortfall requires stimulating global demand for labour on the continent. This is a big long-term focus.

- Inclusivity focus: Jobtech can help include groups that traditional labour markets often marginalise – such as women and refugees.

What have we learned so far about applying systems change across Jobtech Alliance?

Jobtech Alliance was started as a systems change initiative and with support from the Small Foundation, the Jobtech Alliance team at Mercy Corps, and BFA Global, have engaged systems change practitioners, Wasafiri, to help more thoughtfully embed this approach into its work. Two early learnings are:

- Importance of shared language and concepts. We have integrated Systemcraft as a tangible and applied framework to help gain shared language and concepts that guide our decision-making and implementation. With so many stakeholders involved across the jobtech sector, building a shared language and understanding of how the system works (and how we interact with it) is critical. As we’ll share soon when presenting our systems change model, we’ve integrated multiple overlapping concepts – how the system works, our theory of change, our workstreams, and our principles (see below) – into one common vision.

- Need to embed systems principles into everything we do. Whilst the Jobtech Alliance team has been doing systems change for a few years, we have never been able to articulate what such an approach (as opposed to ‘activities’) really means. We were missing some simple, high-level guidance that recognised the interconnected nature of what we do and helped us maintain our mission and character as the Alliance grows. We therefore developed ‘Principles’, which have allowed us to identify blind spots in activities and workstreams and be more comprehensive in our work, from new country engagement strategies to the newsletter and planning events.

What’s next, and how to get involved

Systems change doesn’t happen in a day, and even though we’re two years into our work, we’re still early in our systems change journey.

Over the coming months, we’ll share our systems change model for the Jobtech Alliance and how we hope to influence this emerging sector.

We strongly believe that cultivating an inclusive jobtech sector that creates and improves jobs across Africa is key to advancing the prosperity of the African population and offers promising prospects for financial returns and social impact. We are building a movement, and we’d love to get you involved.

To get started, please head to our website to Join our Community.