Faster food system transformation: why it’s more art than science

Latest posts

Share:

Changes to the way our food is produced, processed, distributed, consumed, and disposed of will rely more on creativity, intuition, and subjective judgment rather than strict scientific principles and methodologies. This is why…

The first-ever UN Food Systems Summit in 2021 provided much-needed impetus to the transformation of African food systems. Countries across Africa are developing policies and encouraging actions to transform their food systems. This is exciting and much-needed work. And I find myself asking key questions:

- Who are the food systems leaders that can make change happen at a scale never seen before?

- What kinds of food systems leadership is needed?

- How can we work together to speed up change?

- Are food systems leaders being supported in the most effective ways?

These questions matter because change is driven by the interactions between people. Science and technology will find their place, but change will come from the priorities we hold, the choices we make, and the ways we choose to work together.

Who transforms food systems?

Transforming food systems requires large numbers of people connecting and collaborating. Farmers, aggregators, truckers, policy writers, regulators, researchers, marketers, and consumers all have a role to play.

Transformative change will only happen if the week-to-week decisions of many millions of people working in areas such as these change.

Two people who exemplify the kinds of people who are making change happen are Tabitha Njuguna, from Kenya and Innocent Bisangwa from Rwanda.

Tabitha is the Managing Director at AFEX Fair Trade Limited Kenya, a private company that provides end-to-end solutions to farmers including input financing and warehousing. With 17 warehouses spread across two counties, AFEX has registered over 11,000 farmers and traded over 11,000 metric tonnes of maize.

In February 2023, AFEX Fair Trade Kenya secured certification of their Soy Mateeny warehouse which marked the first time a warehouse receipt operator license has been issued to a private company in the country. This will open private investment to local farming, playing a vital role in fostering sustainable and resilient food systems for coming generations considering the growing population and the demand for food only going up.

When asked what major hurdle needs to be overcome in food systems transformation, Tabitha says, “Increased production costs means reduced production or a compromise on quality which trickles down to the food on our tables. Providing affordable, accessible, and timely financing for farmers is critical.”

Innocent on the other hand, works for Rwanda’s Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources (MINAGRI). As an environmental and climate change specialist with experience in sustainable agriculture advocacy and policy development, he is currently working on the My Food Is African campaign that aims to mobilise for an African food policy at the national level across the continent.

It is calling for Africans to shape the food systems and policies that enable (or disable) this access to healthy food for all. He has also been instrumental in the Irrigation Strategic Plan and the Post-Harvest Strategy, both in Rwanda.

Innocent recognises that policy and systems-change leadership are intertwined. “A food systems leader is one who recognises their skills and capacity and uses it to support systems-level change.”

What kinds of leadership do we need?

Changing food systems requires amplifying the potential of leaders such as Tabitha and Innocent. They work towards significant transformations, making progressive decisions within the existing limitations.

Change requires passion. It requires determination for the long haul. It requires bringing a form of food systems leadership that is diverse, reflective, relational, contextual and doing the work collaboratively in the here and now.

How can we speed up change?

Change is often slow because there is resistance to it. Can we speed it up?

Food systems leaders must be willing to ask difficult systemic questions like: ‘Who is the system working for?’ Answering this shows us where resistance sits; and where we need to focus our efforts.

Many national food systems around the world appear broken. But they aren’t broken. Rather, they are inequitable. Some people lose out, and some people gain. Let’s take examples inside and outside Africa:

- In Kenya, most people get their food from local micro and small enterprises. If these enterprises could bring healthy and sustainable foods to local markets in greater numbers, they could be a big part of the solution. The new Government speaks of its support for small businesses including with a Hustler Fund – this creates a climate for change.

- While in the UK, there is ample evidence the food system is not working in the national interest, notably for the long-term health of the population and the environment, but traditionally a steady supply of affordable food has been achieved. Brexit provides a unique opportunity for radical change, notably for environmental benefit in balance with peoples’ needs.

A systemic change in all food systems will happen faster when efforts are made to wire people together in new ways that in turn spark new forms of collaborative action. This is true in Africa and beyond.

Change happens when interactions build shared goals about changes that are needed; and when the ‘change that is needed’ becomes widely understood and grows in significance among targeted decision-makers.

It happens when the incentives decision-makers need to create a new path become strong enough to trigger action; and it happens when intelligence about what is going on in the system and about the change that is needed, is shared in an equitable way.

How to support our food system leaders at the front line?

One of the things that make changing food systems hard is that these systems often involve a lot of different actors who don’t have mechanisms to connect with one another. This makes it hard for farmers to effectively influence policy, or for institutional food buyers to influence food producers or national researchers to connect with regional food markets.

Without these kinds of unusual connections, it is hard for progressive food system leaders to connect and collaborate in new ways to help them accelerate their efforts to transform food systems. How can this change? Let’s look at one model of doing this.

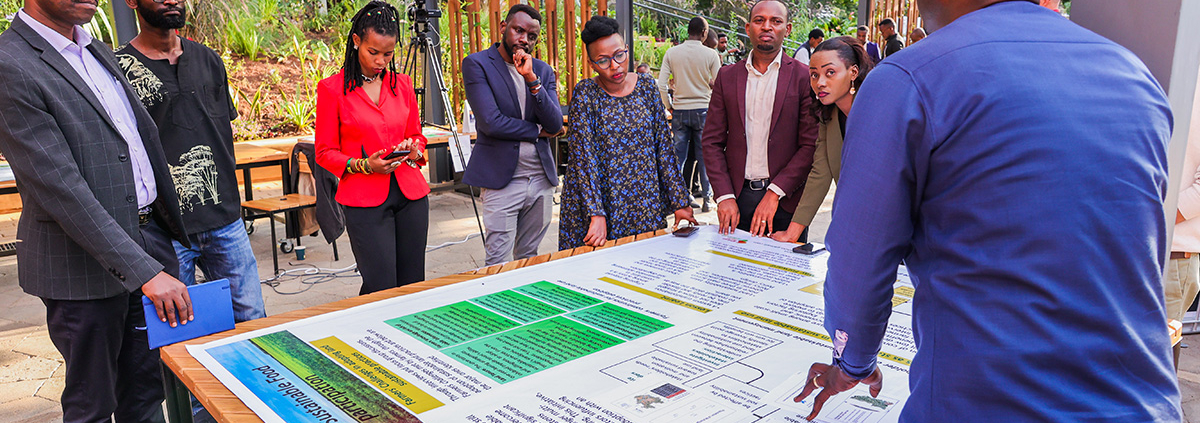

In 2020, Wasafiri and Wageningen University and Research wondered: Could an African Food Fellowship support a new generation of food systems leaders to build more inclusive, healthy and sustainable food systems across Africa?

With support from the IKEA Foundation the African Food Fellowship launched with a focus on Kenya and Rwanda but oriented to a continent-wide ambition.

Three aspects mark the African Food Fellowship as innovative:

- Participants are selected for impact. Fellows are selected for diversity and in combinations that are most likely to achieve practical impact together. The Fellowship targets participants within sectors of food systems (e.g. horticulture) and it builds up a network of Fellows in each of these areas over multiple years connecting public/private/civic sectors. For example, we are building a network of Fellows in the aquaculture sector in Kenya and from this multistakeholder collaboration early positive results are emerging: Aquaculture collaboration.

- The first Food Systems Leadership Programme: The African Food Fellowship designed and has demonstrated the value of the world’s first action-oriented Food Systems Leadership Programme. The 10-month programme curriculum includes world-leading food systems foresight and Systemcraft to equip leaders to drive transformational change. The Programme enables participants to understand food systems and advance food systems actions collectively as Fellows and separately to the Fellowship.

- Curating impact networks: Most of the energy and resources are focused to nurture ‘impact networks’ of Fellows from Rwanda and Kenya. The Fellowship encourages self-organisation. It promotes conditions for Fellows to advance food systems actions collaboratively and independently. While this is early days; there are encouraging signs: Goat project for disabled by economist Suleiman Kweyu African Food Fellowship wins.

If nurtured well, the Fellowship can become a diverse and powerful professional network of thousands of food systems leaders operating across multiple countries agitating for change and providing practical pathways for doing so.

The art of supporting diverse and progressive leaders

Food systems can be healthy for people if led and managed well. And they can provide good financial rewards for those working in them and be sustainable for nature and the climate if led and managed well.

We will greatly accelerate progress if more resources are focused on the art of finding, connecting, and actively supporting the diverse and progressive food systems leaders, who can make radically different decisions about how businesses operate, what food-related policy contains and so on.

Cultivating food systems leaders to make different decisions in every country, and in large numbers, is how we can transform food systems faster and better. Let’s find ways to make it happen!